When popular education pursued the liberation of marginalized und suppressed population groups as its principal target it could not help looking at the situation of women who were, and still are, suppressed in more ways than one. On the one hand, they share the marginalization of their social class, and frequently of their ethnicity. But in addition, traditional social order deprives them of basic rights and makes them subordinate to men. This is the ground for gender education as an integral strand of adult education. Imelda Arana Sáenz, a Colombian sociologist focussing in particular on women studies, describes the creation and development of the successful Latin American network for women’s education, REPEM.

REPEM, the Red de Educación Popular entre Mujeres was created in the early 1980s, initially as a working group of the nascent council of Adult education in Latin America – CEAAL, driven by the initiative of some of the women members of partner organisations of the council. this is the period when the eP, educación Popular (popular education), movement gained strength in the region, emerging in the 1970s as a current of social thought and action that sought to contribute to the political, economic, social and cultural transformation of the region. It was marked by long periods of dictatorship, where the problems of women did not appear as a central focal point for reflection and analysis, let alone for political action. the women at the core of the emerging rePeM forcefully influenced the thinking of popular education in the context of “education as a practice of freedom” led by Paulo Freire, feeding it and contributing to the development of this current of thought and practical action of eP and broadening the perspective of EPF (Educación Popular Feminista, feminist popular education) in the region.

In 1981 REPEM established itself as an autonomous organisation in an environment of reflection, discussion and questions about the difficult relationship that involved the feminist leaders of popular education who were trying to broker against some practices and assumptions that did not fully take into account the conditions and realities of women. the organisations that constituted this network then deployed an important conceptual basis starting from the analysis of the relationships between education, economy and development as well as between education, empowerment and the active citizenship of women. the actions of the network then focused on the development of the processes of training and education among women, of political advocacy with a feminist perspective for political, social, economic and cultural empowerment of women and for the improvement of the conditions that sustain the discrimination, inequality, violence and poverty they faced in the different countries of the region.

As a network of popular education among women, REPEM held collective processes of coordination, reflection and analysis among the groups working from the perspective of popular education “with, from and for” women in the region. From there, the relationship between popular education and women’s rights constituted the engine that drove the search for a perspective that linked these two aspects of social and political action of women’s organisations operating within eP. they raised the prospect of “popular education among women,” which then became EPF (feminist popular education). the tensions between “feminism” and a “popular movement” as thinking and as a field for political mobilisation encouraged the grassroots women’s organisations and the feminists who worked with them to seek further explanations about the situations of oppression that affect women in their diverse cultural and social situations as well as new forms of political practice in line with the conditions of female participation, so that they could participate freely politically and gain access to power on a par with men who share their struggle for collective rights. the similarities and differences between the men and women involved in this struggle are present in every quarrel with the dominant powers and oppressors, where the achievements attained are rarely specifically beneficial for women.

When women as a group reflect on social practice, they notice the fact of low visibility of their own demands in the various educational activities undertaken by the popular education (EP) movement. the absence of analysis of the conditions of women, about their particular situation, their needs and their position in society leads them to think, organise, conduct and organise instructional strategies and pedagogical practices appropriate to the female population and, through them, thought and feminist politics are incorporated to realise the perspective of feminist popular education – EPF – which allows the processes of education, training and empowerment of women to make possible the analysis of oppression, subordination, the exclusion they experience as well as the multiple discrimination they are objects of, especially based on class, gender and ethnicity as part of building a way of viewing education as a practice of freedom. the experiences of feminist popular education question the traditional education system and promote cultural change, establish a dialogue of knowledge that favours the identification and valuation of the knowledge of the people and of their women.

REPEM is a feminist network and as such endorses the strategy of “politics among women” which encourages feminist groups in the world to start from their organisational experiences,

Promoting gender awareness and training, which strengthens their ability to manage their autonomy in society and increases the power of women and their organisations as political entities. through political practice “among women” and “starting from there”, the network is able to establish and strengthen methodologies and practices of individual and collective empowerment that gather interests shared by the “networked” organisations and are constituted in the postulates of feminist popular education, including:1

The rescue of knowledge and experiences of women; arrogation as the starting point of the reality of women, their social practices and daily life; reflection on these things and how they can be turned around in order to transform them. In summary, the deconstruction of androcentric ideas and concepts that for centuries have undervalued, and made women invisible and unknown as social and political actors and as entities that have rights.

REPEM Meeting Source: Imelda Arana Sáenz

In recent decades, social movements, and especially women’s and feminist movements, have favoured the articulation of networks and alliances. networks allow the building of relationships in spaces near and far and between one another; they allow local, national, regional and global linkage to achieve agendas and to make struggles communal; they contribute to the articulation of interests, the achievement of which demand the sum of and the strengthening of joint efforts between multiple actors and stakeholders. networks allow the maintenance of cohesion between organisations and the women associated with them without compromising the autonomy of the organisations that comprise them, holding firm to the bonds that unite, as well as to the web stretching in the direction of the regions where different nodes converge. the network is also a source of mutual support between women

and organisations, keeping alive common goals, sharing experiences on shared issues, facilitating the development of joint projects and actions, which does not mean they all think, act and talk similarly, or that there are no differences or discrepancies. It is that they constitute a source of skills and theoretical and practical potentials which strengthen the advocacy power of the network.

As regards REPEM, the network also responds to the need for women’s groups to have autonomous spaces for sharing knowledge and for personal and collective learning, with a view to strengthen and enrich the social and political practices and life itself for women and “between women”. the training strategies and knowledge production which have been produced in the network have given visibility to the work of popular education among women and have made the various activities of the network learning spaces and places where processes can be developed. From this perspective, the network has proven to be the most favourable form of organisation for the joint purposes which are characteristic of a network of popular education and for the operation of the organisations of women who constitute REPEM.

The diversity of backgrounds, life experiences, levels of academic training, personal stories, socioeconomic and cultural realities, ages, interests, personal assets, families, among other realities, makes rePeM a very large group of human beings, diverse and complex, who, in order to successfully negotiate actions to achieve shared aspirations, had to coalesce in an entity that respects the diversity of the levels of commitment, the variety of time and resources that each can provide, the expectations that each group and each woman has on the actions of the organisation as a whole. All these obstacles have been bypassed through the possibilities offered by a network, where there is individual responsibility, along with collective commitments, where each organisation and each woman gives to the extent of their conditions and possibilities, where there are leaders with authority, who are elevated by the groups to be their spokespeople at times and in front of key institutions, where there is expertise in various fields of human activity, where there is solidarity and complementarity in the work, where hierarchies regarding the coordination of structures are rotated and temporary, where no one works for pay because other non-monetary compensation takes place, where learning among women is the vista for personal and collective growth and benefit.

In its political and cultural activities, rePeM has had to enter the field of global culture, and what constitutes a challenge in the prospect of the network is “the space” where feminist popular education and women’s rights, in the local, regional and global context occurs. they have had to do this with a logic that keeps a balance between the need to develop operating guidelines, with clear procedures, and the imperative to carry out actions with flexibility, agile responsiveness and creativity in order to confront de facto situations and the various proposals it receives, while preserving participation, including the democratic life of the network.

The mechanisms used to maintain the dynamism of rePeM as a network have been numerous and have been changing as the social life and the processes of interaction and communication have been transformed. undesirable effects in organisational life have been perceived as a result of the changes. Although processes can be completed expeditiously and in a timely manner through the use of new technologies, they have brought collateral damage to lives and relationships, both interpersonal and group relationships. In addition, women and organisations that for various reasons fail to catch up with new media and virtual logic are being left out and left behind on the road.

Globalisation causes situations that facilitate the flow of information, goods and opportunities, which cause changes in social relationships. For connected citizens, it creates possibilities to enable global transnational movements that vindicate assumptions regarding issues such as diversity, autonomy, freedom and the right to good living. the feminist movement is now in this new arena, making use of networks as relationship “strategy” and as a “medium” of information and communication, to give potential to its political, activist, social and cultural outreach. this has facilitated the coming together between the various expressions of the feminist movement, between these and other women’s organisations as well as coordination with other social movements, environmentalists and ecologists and between gender and sexual diversity advocates as well as ethnic groups and races, unions, and youth groups, among others.

The actions undertaken by women’s networks to strengthen and enhance their work in these new arenas have been multiple, including: construction and coordination of agendas, coordinated political advocacy, exchanges and internships, identifying and disseminating best practices, creating virtual spaces for deliberation, the facilitation of virtual and real training spaces, the production of parcipitative research methodologies that provide information for the exercise of political action, the creation of lists, chats, blogs and the use of social networks, among many other things.

Notwithstanding the benefits of the resources, questions have emerged internally in rePeM about the meaning and relevance of networks built on new technologies, with a great flow of information and news that is produced in real time and doesn’t allow for expectations or time to think about mechanisms to achieve a balance between democratic and inclusive “being”, efficient and effective “doing”, and the “thinking-learning” that takes place in reflection and the creative and deliberative collective. this raises questions about whether the networks are still weaving a social fabric of democracy and solidarity, and if it is possible in these times, and how to maintain this spirit when the speed of communications create an agenda that does not assimilate, let alone allow time to socialise.

The question also arises about whether it is possible at present to keep thinking of “balanced processes of articulation” between being, thinking and doing, that contribute to the achievement of social, economic and gender justice in a network structure where the educational dimension is the strategic element for achieving gender justice. this is the big question that rePeM now asks itself, because its membership still counts on networking as a necessary strategy for the advancement of their rights, work that should result in a dialectic in which people, the groups and local populations strengthen each other and grow in the broader relationship and articulation: the networks.

The fact of being in an entity comprised mainly of women’s organisations, including many sectors of the populace, gives a very strong impression of self-management. the ability of women to manage resources and to use those that come under their responsibility in a reasonable and equitable way is enormous. this regards the assets of those affiliated with rePeM who have been a source of resources and funding which was unaccounted for and sometimes not properly recognised by their own members. Besides that, networking helps to minimise costs and generate economies of scale in every action and every matter of daily activity, reducing business transaction costs to implement the proposals. And in the field of new technologies, the value of representation is maximised, while the costs of representation and leadership are minimised.

At the present time, and in the experiences described above, the members of rePeM have had to manage and negotiate new resources in regard to international cooperation, especially for institutional strengthening and sustainability of the network, since there are no conditions for establishing maintenance fees to guarantee stable funding for any of their activities. there has been great support from aid agencies and ngos from european countries sympathetic to the practices of popular education and mobilisation for the right to education and literacy of adults.

These international agencies, intergovernmental and global ngos that support the struggle for women’s rights and/or the struggles for the right to education have also provided support for specific activities. the formation of alliances with mixed or women’s organisations for the organisation of, or participation in international events has allowed the management of resources that have enabled the international presence of rePeM at conferences and follow-up meetings of international education, Adult education, women’s rights, development, population, as well as in global and Latin American women’s conferences.

Today, women’s organisations in Latin America and the caribbean are facing financial uncertainty created on the one hand by the lessened interest of the various united nations agencies and of the international cooperation issues related to women “without means”, i.e. without tying it to poverty, war or calamity, and on the other hand because of the economic and structural crisis europe is going through, where significant resources for cooperation emanate from.

In the end, added to this is that, even with the facilities that provide virtual networks, a diminution of opportunities for actual meetings among women is evident, which thereby increasingly affects the participation of women in the most remote and still excluded sectors, and the benefits of global growth of new information technologies will deepen the digital divides that have shaped social, economic, political and cultural inequality, with specific impact on the situation of women.

To find economic cooperation and solidarity for the construction of relationship spaces and network organisation is becoming increasingly difficult.

REPEM, thanks to the experience of 30 years of networking among women, currently includes 140 organisations – ngos and grassroots – from different countries of the region, with strong organisations in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, chile, colombia, costa rica, ecuador, el Salvador, guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto rico, dominican republic, uruguay, and Venezuela. Several of these organisations are also members of ceAAL with which ties of cooperation and joint action are thereby maintained, these being the two leading organisations of popular education and education of young people and adults in the region.

In its 30 years of life, rePeM has positioned itself in the region for its presence in advocacy activities, both nationally, regionally and globally, including: a) the world Social Forum, which is part of the International Board and national and topical Hemispheric Forums; b) processes for tracking and monitoring of the world conferences on education and the goals of education for All – eFA, youth and Adult education and literacy campaigns – as well as accompanying the global campaign for education; c) actions that fall within its mission around the conferences against racism and racial discrimination, conferences on women, development, population, ending violence against women, the funding of development, the call  to Action Against Poverty, from the Feminist working group, the campaign for the decriminalisation of Abortion, the Forum for democracy and cooperation, integrating the International committee tied to regional, Latin American, African and Asian networks, as well as to the ecLAc conference of women.

to Action Against Poverty, from the Feminist working group, the campaign for the decriminalisation of Abortion, the Forum for democracy and cooperation, integrating the International committee tied to regional, Latin American, African and Asian networks, as well as to the ecLAc conference of women.

Information desk of REPEM

Source: Imelda Arana Sáenz

1 excerpts from the text “Foundations of the working group on education, gender and citizenship GTE”, input preparation for the Sixth general Assembly and the commemoration of the 30th anniversary of rePeM in november 2012.

2 Jeanine Anderson. “How to build women’s political assets.” rePeM Assembly. March 2004.

3 (Ibid).

4 (Ibid).

5 Included here are excerpts from a document systematised by Janneth Lozano B., with input from the writings of Jeannine Anderson, cecilia Zafaroni, Iliana Pereyra and Herlinda Villarreal, members of rePeM. Bogota, August 2011.

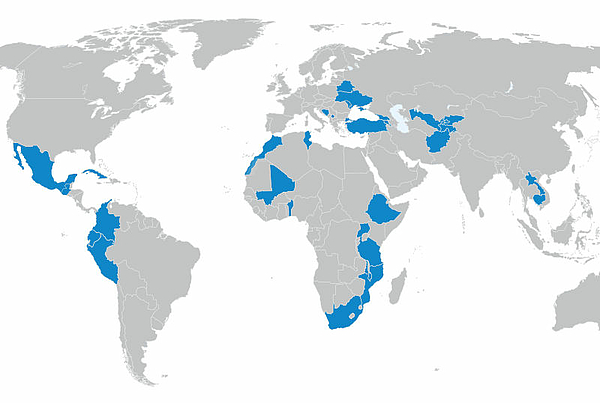

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map